Advancements & Achievements« Back to Advancements & Achievements Listings

South African Graduates Unveil the World's Most Advanced Low Cost Hand Prosthetic

The Development of “Touch Hand” Illustrates the Urgent Need to Empower SA’s Top Student Innovators, and For a New Go-to-Market Support System for Post-Grad Entrepreneurs at SA Universities

By Rowan Philp

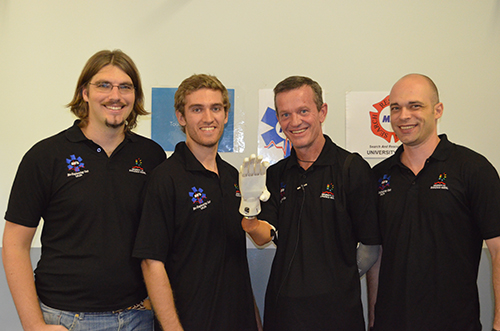

A small team of South African post-graduate students has developed the most advanced low-cost hand prosthetic in the world, with a 3-D printed product set to disrupt the medical device market.

Offering a unique modular system - customized to each amputee’s physical needs and budget – the award-winning “Touch Hand,” developed by students at the University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN), is to be marketed at one tenth the cost of similar bionic hands on the global market.

Its 27-year-old creator, Drew van der Riet, said he was “astonished and dismayed” to find that the vast majority of upper limb amputees still used “claws” or nothing at all - and that western companies were charging, on average, well over R1 million, or more than $80,000 USD “for the basic functionality and dignity of a myoelectric prosthesis.”

He said users fitted with the Touch Hand are able to pick up both delicate and irregular objects, thanks to advanced microprocessors that react to forearm stump muscle movements to drive tiny myoelectric motors. A sensory feedback system from the hand itself is another modular feature to be added soon. This unit is the first to use low-cost, 3-D printing for a myoelectric prosthesis. Drew’s preliminary research suggests there are 1500 new upper limb amputees in South Africa, and approximately 200 000 globally.

“For investors, the modular aspect – customizable to each amputee’s budget - is a really significant value proposition,” Van der Riet says. “The hand will also include an innovative control algorithm allowing the amputee to select from a large library of grip types and gestures without any need for manual configuration, unlike currently available prostheses. But far more than the business aspect: amputees clearly feel they are being taken advantage of, being asked such ridiculous prices for technology that is readily available. Companies are charging $100,000 for basic functionality – it made no sense to me. We were making 6-motor hands for $1,000 in the lab!”

Mechanical Engineer Patrick Booth-Jones – a judge at the 2014 South African Institute of Electrical Engineers Graduate Innovation Competition – said Touch Hand was primed both as a profit driver for investors, and as a major potential humanitarian solution, via collaborative platforms like CauseTech.

This is a collaboration between UNICEF, BPI and the Chief Marketing Officer (CMO) Council, which is already linking technology innovations with targeted needs for the most vulnerable children, and Van der Riet said he was eager to investigate ways to transform the lives of upper limb child amputees through CauseTech.

Booth-Jones said: “It’s increasingly clear that low cost technology solutions using a modular integration approach, smart design, and up-to-date current manufacturing techniques are our forte as South African innovators. What Drew has done could represent a game-changer and a life-changer for amputees in emerging markets in particular.”

South African innovation for disruptive cost reduction includes everything from Kobus Meiring’s passive ventilation large telescope designs, and the open-source load balancing products by IT start-up Snapt (at 3% the cost of US rivals) - to HelloCrowd’s unique rental model for the mobile events app industry, and Elon Musk’s efforts to cut the costs of space launch by a factor of 100.

Touch Hand follows a South African pedigree in medical device innovation that extends back to the co-invention of the CT scan, and out to the development of nanotechnology to prevent drug resistance deaths by automatically delivering TB drugs to target cells.

However, despite a market of critical need globally among tens of thousands of both poor and higher income amputees – Touch Hand, like so many world-class South African tech innovations, remains on the commercial launchpad.

Booth-Jones says the lack of an institutional support structure “post graduation” for innovative products is stifling world class careers and products in technology.

“Universities in South Africa are good at research, but there is a great divide between engineering research that produces great innovation, and taking your innovation to market - where you need a whole new set of skills, experience and resources that graduates do not have,” he says. “I judged about 20 top innovations by students from the country’s Universities and Technicons last year – many were truly innovative and certainly commercially viable, it’s just extraordinary what these guys had created. But they said – ‘its great to get a masters (degree), but there is no help beyond that’. Those institutions and South Africa as a whole is losing out as a result. Graduates just lose interest without support; many feel they have to leave to pay off their bursaries.”

A major 2007 audit on biotech innovation by the SA Medical Research Council found that the chief barriers to innovation in the field in South Africa were: the time and costs required for regulatory approval; access to capital; access to international markets; lack of protection of IP; and access to technology.

Van der Riet said the tertiary lack of capacity saw Touch Hand lose one its core designers, Greg Jones, just last month. He said: “In my final (masters) year, I was surrounded by relics – amazing innovations that were just sitting there, gathering dust, and universities don’t seem to realize that they are sitting on a goldmine of technology, or don’t have the know-how to get behind that.”

A pathway to the solution was dramatically demonstrated earlier this year, with the development of a revolutionary prototype HIV diagnostic test by graduate students at Rhodes University, now supported by UNICEF in a game-changing collaboration.

Using a 3-D printed case, a bio-recognition agent, an inexpensive test strip, and an ordinary smartphone, the Colorimetric Aptamer Based Biosensor can accurately measure patients’ CD4 counts in under 20 minutes – removing the need, and risk, for patients to return to clinics for their treatment course following their HIV diagnosis.

The key to this life-saving success, however, was an initiative at Rhodes to retain graduate students after the completion of their academic studies, and to provide them with physical space and resources to turn their research into products through the new Biotechnology Innovation Centre. Its director, Professor Janice Limson, is now leading the call for the creation of an innovation space at SA universities which serves as “a bridge between research and product development” – as described in this recent SABLE feature.

Booth-Jones said this new model could transform the innovation and revenue potential for both local universities and disruptive products like Touch Hand – and he said the new enabling capacity would require only a small investment.

He said: "There should be a bridge between products developed in a post graduate project, and an incubated or small startup company that has saleable product and some market penetration. A design that comes from a postgraduate project is nowhere near ready for market. It requires re-design, re-making and refinement. At least three or four more prototypes need to be made, including several related processes that have to be developed before a pre-production version is ready. This 'post R&D' phase does not require large investment - often it is only a few salaries and fixed costs for a year or 18 months, some third party processes and minimal equipment. This is the twilight zone between the University’s scope of responsibility with research, and a small start-up company taking the outcome of R&D to market."

He added: “A product such as the Touch Hand would, in my estimation, require only another year and perhaps three more versions to be produced before it is ready for pre-production. Early customers can be encouraged to try “Beta” versions at a lower cost which gets the product out there and on the way to maturity.”

Born in Port Elizabeth, Van der Riet emerged as a solution-oriented innovator during both his undergraduate and post-grad studies at the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University. Booth-Jones was a key mentor: “Drew was one of those wonderful young men who go through the metamorphosis in their fourth year and emerge as engineering professionals. It was my privilege to introduce him to the mighty micro that is changing our world. When I discovered what he was doing (with Touch Hand at UKZN), I immediately thought of the SABLE Accelerator as a means to achieving something potentially of great benefit.”

Having graduated from NMMU, Van der Riet embarked on sabbatical, teaching English around the globe, from Georgia and South Korea to Chile. He said the experience added a humanitarian element to his existing focus on technology and entrepreneurship.

“My interest in medical devices started with my final year project at NMMU, where I developed an exoskeleton hand which could improve grip strength for its wearer – such as people with arthritis. I really enjoyed the very personal aspect of the field, and after travelling around the world I knew I wanted do something in that area.”

He added: “Beyond functionality, what struck me is that one of the biggest problems amputees suffer from is depression, or a fear of standing out in a crowd, visually. But we have the technology to address those challenges, and do it affordably. In Durban, there is not a single amputee with a myoelectric hand – these folks are using hooks, or nothing at all. Advanced hands are simply too expensive, and in South Africa, medical insurance companies don’t pay out nearly enough to cover the cost of hands on the market today.”

He intends to register patients both for the modular design and the sensory feedback system.

Van der Riet said: “I was first pushed towards entrepreneurship after attending a free entrepreneurship training workshop hosted by TIA - the Technology Innovation Agency - and used these newly acquired skills to secure a R500,000 seed grant through UKZN from TIA.”

However, Van der Riet said this welcome grant was initially restricted to equipment costs only, and was only later amended to allow 40% to be devoted to human capital after strong motivation - “and we would have ideally spent 80% of it on that.” He said this de-emphasis on the core challenge of human capital - “by far, the greatest expense for most innovators” – illustrated the need for further refinements in South Africa’s enabling environment for entrepreneurs.

Although Van der Riet said he would welcome assistance with a revised business model, his earlier business plan calls for a sales gross margin of 80%, and requires funding in the range of $2 million to fully commercialize and disrupt the market space.

Check out The Touch Hand blog to learn more about how this innovation is giving people the tools to shape their own destiny.